The following excerpt is from Designing the User Experience of Game Development Tools, Second Edition, by David Lightbown. The book is now available and is published by CRC Press, a division of Taylor & Francis, a sister company of Game Developer and Informa Festivals. Use our discount code DIS20 at checkout on Routledge.com to receive a 20 percent discount on your purchase.

Excerpt:

B. Hiding in Plain Sight

Did you know that you may have already been aware of some design concepts and how they apply to game tools before you ever read this book? It all comes from a familiar source that has been right in front of you this whole time: games!

Competitive games where speed and accuracy are important – like real-time strategy and fighting – can help us understand many different user experience concepts that can be applied to tools. Let’s go through a few of these concepts, and you might be surprised to find that you know more than you think!

Real-time Strategy Games & Chunking

First, let’s look at how knowing real-time strategy games could mean that you might already understand the concept of chunking[1].

BoxeR the Brood War Champion

One of the all-time greatest players of Starcraft: Brood War is BoxeR. Amongst the many skills of a professional Starcraft player is the ability to build exactly the right type and number of units to defend against an attack.

Starcraft – like many great RTS games – has a “rock paper scissors” design where each unit is strong against certain units and weak against others. What this means is that if BoxeR’s opponents attack using units that are the equivalent of scissors, BoxeR quickly defends with units that are the equivalent of rock, not paper.

Figure B.1: StarCraft © Blizzard Entertainment

For example, imagine that BoxeR’s opponent is playing Zerg and they attack with a combination of Mutalisks and Zerglings. This composition is so common that it has a nickname: “Mutaling”. When BoxeR sees this, they immediately start building Siege Tanks and Marines, since they are very effective units against that composition.

So, how is BoxeR able to do this so quickly? In large part, it is because of their ability to effectively use chunking.

Figure B.2: Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Chess and chunking

One of the best demonstrations of chunking and games comes from a replication study[2] done by the psychologists Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons[3].

In their study, they showed participants a series of cards, one at a time, each with a picture of a chess board with pieces in different positions. They would give the participants 30 seconds to study the card, and then take it away and ask them to place chess pieces on a real board from memory in the same positions as on the card they had just seen.

The skill level of the participants in the study ranged from novice players to grandmasters. For this reason, it might not surprise you to learn that, for certain cards, the grandmasters were much better than the novice players. However, you might not expect that for some other cards, the novices were equal to the grandmasters. How could that be possible?

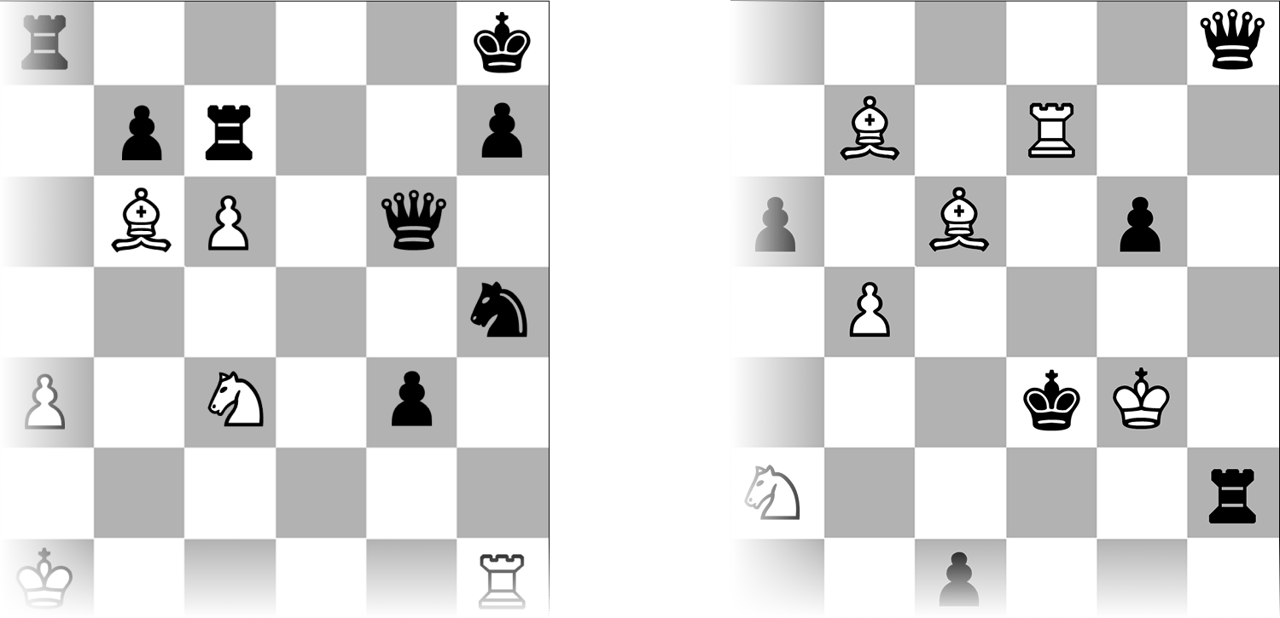

The reason is that the cards where the grandmasters did better than the novices were cards of real games with plausible chess positions (left side of Figure B.3), and the cards where they were equal to the novices were cards where the chess pieces were randomly placed (right side of Figure B.3).

Figure B.3: Representations of the cards used in the chess study.

From the perspective of the grandmasters, the boards on the cards are not made up of individual pieces but “clusters” of pieces in positions that they have seen in countless games of chess (left side of Figure B.4). Over time, these are internalized as chunks.

The cards with randomly placed pieces, however, could have impossible scenarios, like two Kings side by side, or two white Bishops on the same color squares (right side of Figure B.4). These are things that a chess player would never see, and therefore could not have internalized as chunks.

Figure B.4: Common two-by-two “chunk” of pieces (left) and impossible or improbable chess positions (right).

So, instead of memorizing the positions of each piece individually, the grandmasters memorized a few chunks that they had already internalized by seeing them over and over. Meanwhile, the novice players who had not developed the same number and variety of chunks as the grandmasters had to remember the positions of most of the pieces individually.

However, when the cards were made up of random chess positions, the grandmasters couldn’t use their chunks to help them memorize the cards. For this reason, they were just as good as the novices.

By now you can see how this applies to BoxeR: When they see the combination of Mutalisks and Zerglings, they don’t see the individual units but a chunk, and that allows them to react much more quickly and build exactly what they need to defend against it.

Chunking the TRS

So how can all these ideas be applied to tools design?[4]

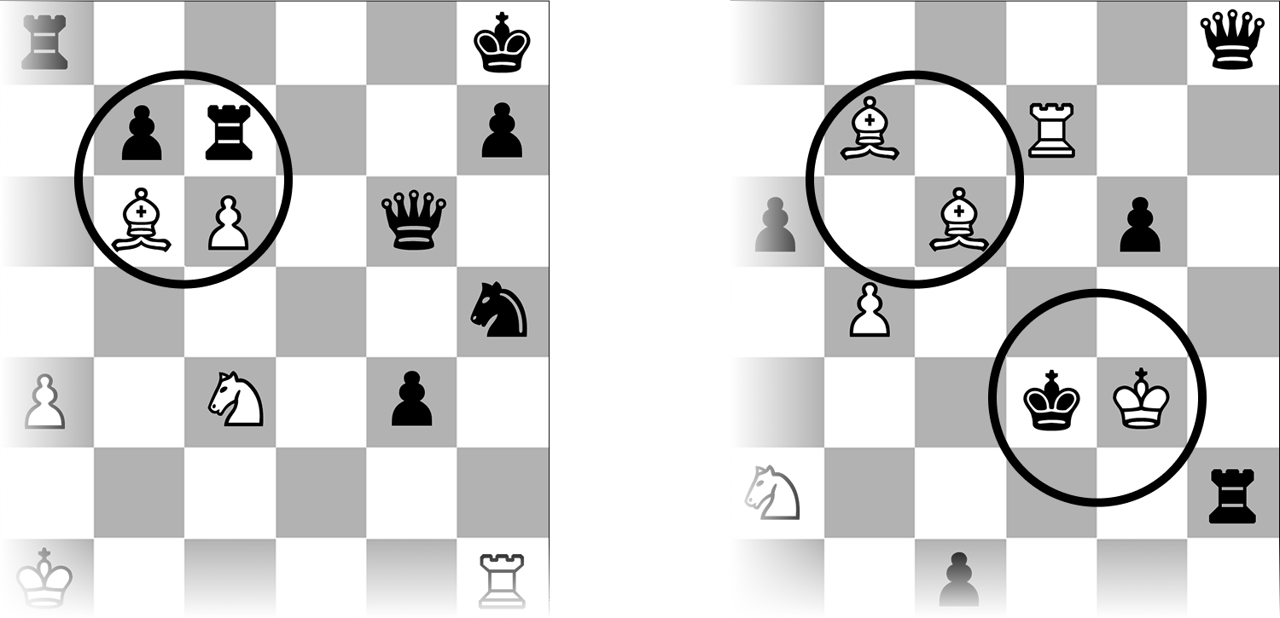

One of the most common user interface patterns in level editors and 3d animation software is the Translate Rotate Scale control or TRS for short. It’s a three-by-three grid of numeric inputs that represent the X, Y, and Z values for translation (sometimes called position), rotation, and scale.

It is almost always seen in the same order: The first horizontal row of three numeric inputs represents the translate XYZ (the position of the object), the second row is for the three axes of rotation, and the third row is for scale (the size of the object).

As people use this kind of TRS control, they start to develop chunks to quickly interpret the numbers. For example, if the first row is three zeros, the second row is three zeros, and the third row is three ones, they know that the object is at the center of the world with no rotation and no scaling (see Figure B.5).

Figure B.5: Default values in the TRS controls for Unity and Maya, © Unity, © Autodesk

However, what happens if the TRS control is not in the same order or orientation? In Figure B.6, you can see that the editor in the game engine Stingray flips the orientation of the numeric inputs to be vertical instead of horizontal, and 3D DCC Softimage|XSI puts Scale first, then Rotation, then Position (Translation).

One of the disadvantages of doing this is that people cannot use the same chunks that they have learned from using another software. So, seeing a first row of three zeros, a second row of three zeros, and a third row of three ones would mean something completely different.

Also, if someone is working back and forth with two different tools (one to create assets and another to place the assets in a level) and the TRS controls in each are different, it could lead to confusion as they switch back and forth.

Figure B.6: The TRS controls for Stingray and Softimage XSI © Autodesk

The lesson here is that it’s important to present data in a consistent order in all parts of a tool so people can chunk it from one part of the tool to the next. If the same data is presented differently in various parts of the tool, it will be harder for users to internalize chunks of information and use them to be more efficient.

Furthermore, if you’re creating a tool that uses the same pattern as another software that the users are already familiar with (like the TRS control), use the same order and configuration so that they can take advantage of the chunks that they have already internalized.

Figure B.7: Photo by Jack Pierce on Unsplash

Fighting Games & Human Vision

Next, let’s look at how knowing fighting games could mean that you already know a bit about how the eyes and the brain work together.[5]

Saccadic Masking

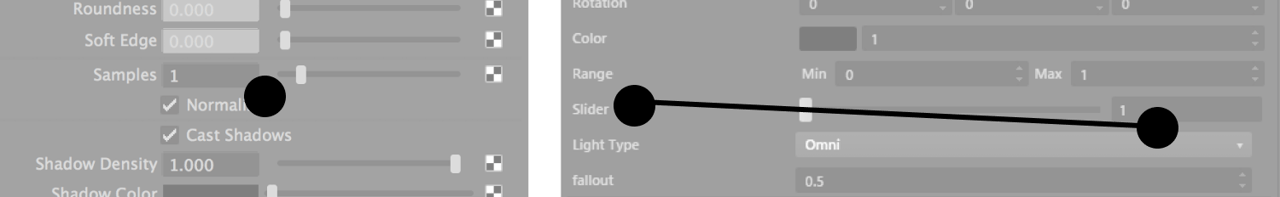

To understand saccadic masking, we first need to understand saccades and fixations. A fixation is the spot where your eye is focusing, and a saccade is when your focus moves from one point to another (see Figure B.8).

Figure B.8: Saccades and fixations

When our eye saccades, our brain temporarily blocks visual processing to perceive the world as stable and reduce motion blur. What this means is that we are blind for a fraction of a second, without even realizing it!

One of the best studies to show the effects of saccadic masking was done by Tim Smith[6]. In the study, he showed participants an image while tracking their eyes using an eye-tracking device. When the device detected a saccade, elements of the image would change or disappear. The participants didn’t notice most of the changes, because they were effectively blind during those moments.

Foveal Versus Peripheral Vision

Foveal vision is sometimes called “central vision”, the part of our vision in the middle that is the sharpest. Peripheral vision is everything else around the center. It is not as sharp as our foveal vision.

Some measurements suggest that the resolution at the extreme edge of our peripheral vision is as low as three pixels per foot (it’s better at detecting color and movement, though). Our brain compensates by “filling in” some of the resolution, especially if it’s something we have seen before. This means that unless we’re staring straight at something, we don’t see it as clearly as we may think we do.

So how does all this relate to fighting games?

Sako and the Sentry

Sako is one of the best fighting game players who is mostly known for their skill in Street Fighter. They are so well known for their Evil Ryu that they even have a combo named after them.

In the early 2010s, the company Steelseries released a device called the Sentry Eye Tracker (Figure B.9) to bring eye-tracking to the gaming community. Its purpose was to help gamers see their eye movements so they could improve their performance. They teamed up with Sako to release a video of him playing Street Fighter while using the Sentry Eye Tracker.

Figure B.9: Sentry Eye Tracker by Steelseries. SteelSeries® is a registered trademark of SteelSeries ApS.

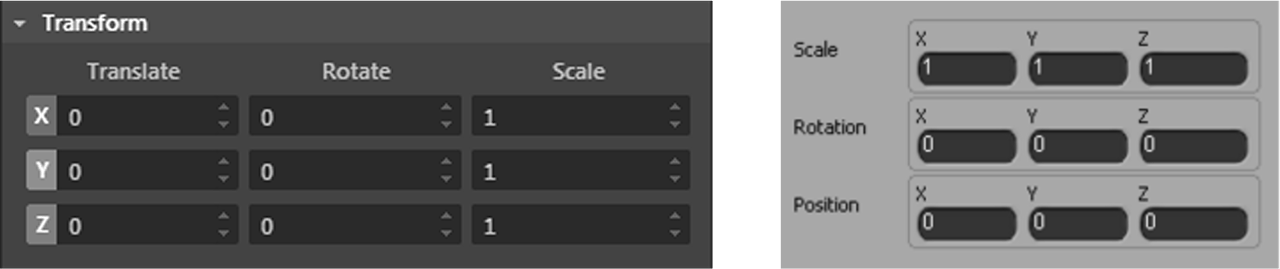

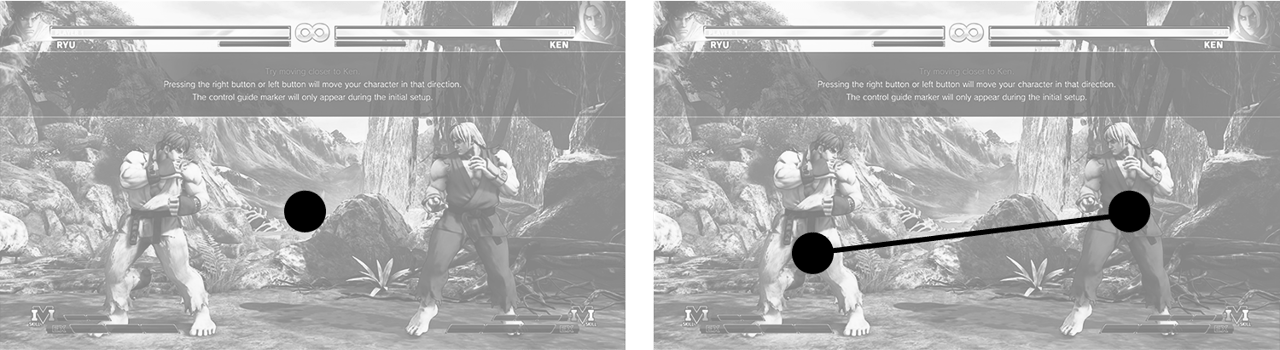

If you watch the video[7], you’ll notice that he fixates right in between both characters (left side of Figure B.10). This is one of the things that separates him from novice players, who tend to saccade and fixate back and forth between both characters (right side of Figure B.10).

By doing this, he uses his sharp foveal vision to keep both characters in focus at the same time which minimizes the number of saccades that he does. This means that when his opponent triggers a move, he’s less likely to miss the first few frames… and when it comes to fighting games, missing a few frames can mean the difference between winning and losing.

Figure B.10: Sako’s eye movement compared to a novice player © Capcom

Additionally, Sako has probably internalized chunks of different poses that both he and his opponent are in, allowing him to read the situation and react ever more quickly (see Figure B.11). Another good example of chunking!

Figure B.11: Chunking poses from Street Fighter © Capcom

Label Placement Eye-tracking

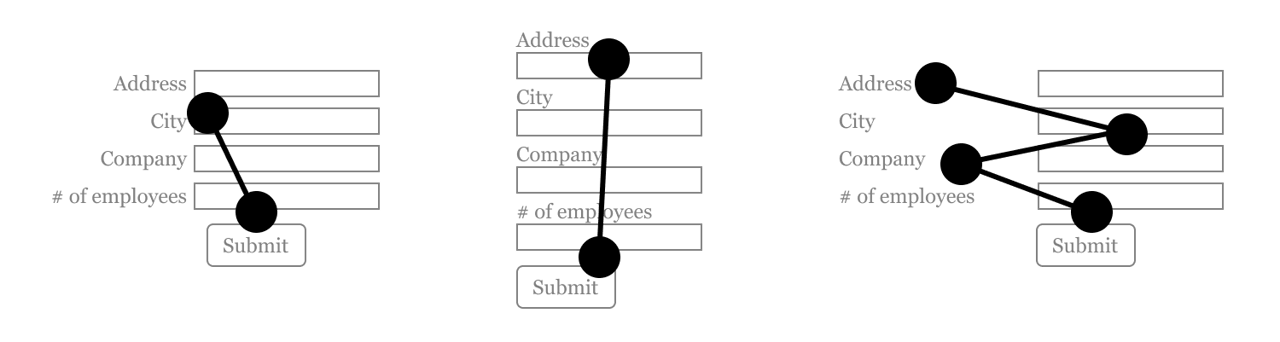

The blog UX Matters has done a series of studies in which eye trackers were used to understand what people look at in various user interfaces. One interesting study[8] compared three different options for placing a label in a form: left-aligned, right-aligned, and top-aligned. Here is what they found.

Labels that were top-aligned and right-aligned resulted in the lowest number of saccades (left side and middle of Figure B.12), meaning that the users were much more efficient at interpreting the data in the user interface. However, left-aligned labels had almost double the number of saccades, meaning that users were moving their eyes around the interface much more than they needed to (right side of Figure B.12).

Figure B.12: Eye-tracking for right-aligned, top-aligned, and left-aligned labels

So how can we apply all of this to tool design?

Forms are very similar to a user interface element found in many of our tools: property editors. They are usually made of a label associated with an input (often a text input, but it can be other types as well).

For example, labels in the Maya Attribute Editor are right-aligned, allowing the user to fixate in the center and read both the label and the value without having to saccade back and forth (left side of Figure B.13). Compare this to Stingray, where the left-aligned labels require the user to saccade back and forth to read the label and the value (right side of Figure B.13).

Figure B.13: Right-aligned labels in Maya versus left-aligned labels in Stingray, © Autodesk

This problem gets even worse when you resize the property editor horizontally, meaning that the labels move even further away from the inputs.

Finally, although top-aligned labels performed as well as right-aligned labels, using them for property editors can be problematic because they usually require the user to scroll due to the increased use of vertical space. They should only be used in situations where there are a small number of inputs. Property editors usually have a very large number of inputs, and so for this reason, right-aligned labels are a better choice.

Wrapping Up

By now, you can see how certain types of games can not only help us learn tools design concepts, but they can also be to explain those concepts to others as well!

Keep in mind, however, that some games purposefully increase friction (see excise in the Design chapter) as a part of the gameplay. While this may be fun in a game, it is not fun when you’re trying to get your work done, so it’s best to look for examples from competitive games where speed and accuracy are important.

So now you know about another great resource that you can use to learn tools design concepts, one that has been hiding in plain sight all this time: games!

Figure B.14: Photo by Hadyn Cutler on Unsplash

[1] We will learn more about chunking in Chapter 5!

[2] The original chess study came from Adriaan de Groot.

[3] You might know them from their study on selective attention, also known as the invisible gorilla video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo

[4] In Chapter 5, we’ll see an example of how chunking can be used to interpret hexadecimal color values.

[5] We will learn more about human vision at the start of Chatper 5.

[6]: Here is a video of the study: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qIF3FRwbG6Y&ab_channel=edz44

[7] See the video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RmAwAefKZ8o

[8] Here’s a link to the blog post for the study: https://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2006/07/label-placement-in-forms.php