“Regionalism” has become a watchword for the game industry in 2025. It’s taken two forms: the excitement over successful games made by developers who draw deep from cultural or national influences, and the multi-pronged effort to reach new audiences in regions like South Korea, Brazil, China, Kenya, and beyond.

Games like Game Science’s Black Myth: Wukong, Sandfall Interactive’s Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, and Shift Up’s Stellar Blade have dominated professional discourse as successful versions of this phenomenon. There isn’t any one way to capture the same lightning in a bottle that those three games did, but Virtuos CEO Gilles Langourieux has an interesting proposal for developers who want to branch out beyond their borders: consider developing “region-specific” versions of your games.

Langourieux shared the idea with us in a conversation at DICE 2025, where we’d been discussing the outsourcing company’s purchase of Umanaïa, Pipeworks, and Abstraction. There was obviously something self-serving about the pitch: his idea was that developers could tap into Virtuos’ network of global studios to let local developers create variants of a game that would appeal to their friends and neighbors.

Does the idea have any merit beyond filling the coffers of Virtuos and competitors like Keywords or Pole To Win? Maybe—but only if developers can avoid pandering to players and not make compromises that favor authoritarian regimes.

Game studios have been making regional changes for decades

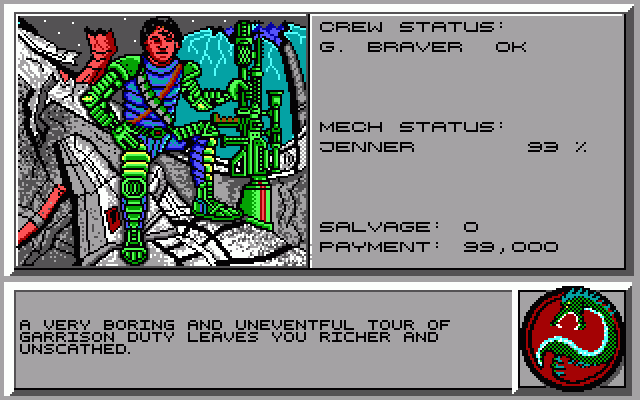

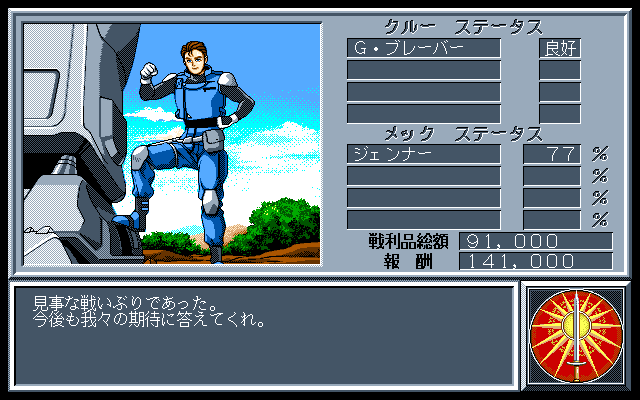

Preparing different versions of games for different regions is anything but new. In 1989 developers like Dynamix prepared different versions of the PC game MechWarrior for MS-DOS in the United States and for the PC-98 and Sharp X68000. Just compare the two “mission completed” screenshots below:

Image via MobyGames.

The two versions have similar foundations—a profile picture of the pilot, relevant statistics, some flavor text, and a clan logo—but there are wide gaps in the UI and art direction between the two images.

Image via MobyGames.

Meanwhile in 2025, companies like Krafton have released regional variants of games like PUBG Mobile in places like India—sometimes after the original version of a game was banned by local governments. Localized versions of games like World of Warcraft or Tokyo Mirage Sessions™ #FE might see (sometimes infamous) tweaks to character costumes or dialogue based on local cultural standards. And there’ve been times when developers experimented with story and characters changes with games like Nier Replicant‘s international version Nier Gestalt.

During our conversation, Langourieux’s vision of “region-specific” game version went a little further than the more familiar approach those past examples represent.

Regional versions of games go beyond localization

“If you compare us to the movie industry, it’s like we’ve not taken the good and we’ve kept the bad,” Langourieux explained. He’d been in the middle of proclaiming that game developers needed to pursue shorter production timelines to match other entertainment businesses like film and television.

“That industry is extremely agile and flexible with how movies are made…we can surely [create] more flexibility with how games are made, because we all know you need fewer people at the beginning of a game, a lot more in the middle, and fewer at the end.”

“If you try to do that with a fixed team, you end up with waste or layoffs—usually both.” He added that remote and distributed development driven by the COVID-19 pandemic makes it easier for teams to build flexibility (that is, if they don’t implement strict RTO policies).

His appeal for agility and flexibility led to the discussion of regional game variants. “The bad thing about the movie industry is that…you can only make one movie that’s the same movie for everybody. In games, we have the luxury to make different games for different people, and too few studios and publishers are fully leveraging that.” He said he’s seen more developers in Asia like Garena and Nexon take advantage of this practice than in the West.

At first it sounded as though he was saying studios should operate like say, Asobo Studio, which makes Microsoft Flight Simulator and the Plague Tale series. The two series target very different audiences. “My thought is that A Plague Tale: Innocence does not have to be the exact same game for people in the US, in Europe, or in Asia,” Langourieux said.

He quickly followed up that A Plague Tale might not be a great example here, and that he was mainly thinking of big budget live service games—but there are plenty of live service practices creeping back into the world of single-player offline games. You have the Early Access model which turns games like 9 Kings and Schedule I into regularly updated games with new features. You have premium games like Vampire Survivors doing brand crossovers with series like Castlevania.

It’s hypothetically possible that with the right team, a developer could release content better catered to a local audience’s needs.

“You have the growing PC install and mobile install base in newer economies like Southeast Asia and South America,” he said. “And that creates opportunities to customize content in order to increase the likelihood of success of the game and earn overseas market share.”

This isn’t a risk-free proposition. Make a regional change without anyone from the area on the development team could lead to inadvertently offensive content or come off as pandering. And the question of how far developers are willing to go in regions where LGBTQ individuals, women, and ethnic minorities are restricted could create unexpected ethical quandaries similar to those we’ve already seen through regional changes to games in places where depictions of homosexuality are banned or restricted.

But Langourieux has a point. The flexibility of digital assets and downloadable updates means the game industry has more agency in globalization than other popular mediums. The main remaining question: can this practice benefit developers not chasing recurring revenue in the live service business?