The following excerpt is from The Game Needs to Change: Towards Sustainable Game Design, edited by Patrick Prax, Clayton Whittle, and Trevin York. The book will be published on November 17, 2025 by CRC press a division of Taylor & Francis, a sister company of Game Developer and Informa Festivals. Use our discount code DIS20 at checkout on Routledge.com to receive a 20 percent discount on your purchase. Offer is valid through March 1, 2026.

We need collective, material, and systemic change in order to meaningfully address the climate crisis. This chapter explains why, and discusses how this approach is foundational for this book and the following chapters. For this, the chapter draws on perspectives from the games industry as well as research results, UN policy documents, and personal anecdotes. After reading it, you will have a framework for meaningful environmental action and you will be able to communicate it to others.

Key take-aways:

-

A framework for understanding and evaluating sustainability efforts in your studio

-

A way to think about systemic sustainability that empowers you to resist greenwashing

-

Stories, industry data, and research results that enable you to communicate this information to a wide variety of people in a way that connects

During a Nordic sustainability game jam I helped organize last summer, a participant introduced herself as the founder of an indie studio. Her studio had been working on games with a sustainability focus and she was excited to deepen her knowledge on the topic. I kicked off the jam with a lecture about the need for systemic approaches to sustainability instead of greenwashing, and in response, this indie founder explained that her studio had gotten funding from Meta. Her mood shifted from excitement about her studio and the jam to something more somber as she explained that yes, her team was aware that their game was part of the broader greenwashing efforts of Meta. The social media corporation, she explained, was funding smaller European game studios to fake a commitment to different areas of sustainability, mostly in order to avoid sustainability legislation from the European Union.

Most centrally, Meta wanted to be able to argue for industry self-regulation instead of legal sustainability requirements for social media and digital platforms, largely so that they could continue their unsustainable practices unimpeded. She clarified that if the giant corporation really had wanted to work for systemic sustainability, then it could have put its enormous weight behind real, material, and systemic means to achieve that. Her excitement about her project visibly dimmed as she explained that their game and studio was part of the calculated greenwashing efforts of a cynical tech corporation. This was tough to see, and it left me wondering how many more game makers are feeling the same way: standing behind their game and its pro-environmental message in isolation, but also realizing that in its systemic context the game studio is even contributing to the greenwashing of a big corporation. There is just no good solution here: Not taking money from Meta to make a game they were believing in is not good either. This is a rock and a hard place, and from the perspective of a single developer, it can feel as if there is no good way of working towards meaningful sustainability.

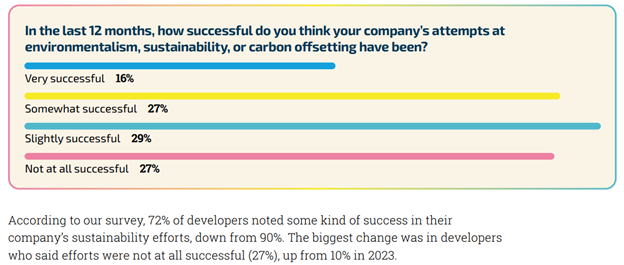

And indeed, we in the games industry are not satisfied with our industry’s climate change and sustainability efforts. This is one of the outcomes of the 2024 State of the Game Industry, produced by Game Developer and the Game Developers’ Conference, one of the most central annual conferences for game developers, report where the number of highly critical responders have risen from 10% to 27% within a year, and where now 56% are answering that the their company’s efforts are either only slightly or not at all successful.

Big tech has regrettably been combating EU regulation for a long time (Doctorow, 2024) and instead favours a self-regulation approach. However, “a critical approach is essential when evaluating Big Tech’s often deceptive sustainability narratives and underscores the need for more rigorous regulatory frameworks” (Vrikki, 2024:1) in all areas, but specifically around sustainability. “disclosure legislation, international soft law and private actors’ corporate sustainability codes of conduct. Despite an abundance of norms, egregious human and environmental rights violations […] continue.”

Figure 1: Game Developers Conference and GameDeveloper.com (2023:24). 2024 State of the Game Industry.

The data that the Game Developers Conference (GDC) & Game Developer shared here also reflects that people in the game industry are well aware of the difference in impact that a small studio can make in comparison to the tech corporations that own the platforms we create and play on.

“Indie studios aren’t the problem. Every indie could go carbon-negative and it wouldn’t change a thing. The real culprits are corporations like Amazon and Microsoft who run massively wasteful data centers.””

This is not to say that game makers and people in the game industry have been inactive here, waiting for bigger actors to move. On the contrary, they have gotten to work: the Climate SIG of the IGDA is one example. This special interest group has been visible at GDC in presentations and workshops, has published their Environmental Game Design Playbook in 2023, and has been running game jams and regular meetings since 2021. The group has also been connecting with research and teaching on a number of intersections, for example by inviting relevant researchers into their meetings and having them write about the process in the excellent Ecogames book featuring a wealth of academic work on game content and climate . Members have been presenting at academic conferences like the Clash of Realities conference in Cologne in 2022 and been running workshops and panels at GDC .

Other examples of the game industry and academia together tackling sustainability issues include a book about the environmental footprint of the game industry with a focus on the real, material world, the Greening Games Project, which presented its final report in 2023 among a number of scientific publications, and Nordic universities have banded together to discuss how to teach about sustainability, resulting in a yearly game jam and exchange that shows students the somber reality and yet still inspires hope and creativity.

The material reality of the games industry is dire. The significant carbon emissions and energy usage of the developers, distribution, and players are only the beginning. Digital games are also made possible by and in turn enable the colonial exploitation of the planet and its people all while normalizing designed obsolescence in the very core of our tech and cultural industries, even though there are recent signs for a move away from this approach. In a later chapter, Busch et.al. offer an extensive overview over the various sustainability crises that games and gaming are connected to.

In summary: We need to radically change the ways in which we produce society on a systemic level to address the challenges of climate change. This also means that we need to take a close look at not only what messages we build into our games, but also at how we make these games. Because games and the industries they are a part of, tech and culture, are so intimately connected to the climate crisis, we also need to examine the context in which they are produced. There is already grass-roots work being done both in building organizations, collecting knowledge, and building connections between research and industry. However, if it is literally possible that entire game studios are the greenwashing of big tech corporations, even while making legitimate sustainability games, then we really need to think outside of the box to reach the kind of holistic and systemic change that we need. In the face of these challenges this chapter asks:

“What would constitute successful and meaningful climate action in the games industry?”

Systemic Change

The report Making Peace with Nature from the United Nations Environment Programme explains that the needed “Transformation will involve a fundamental change in the technological, economic, and social organization of society, including world views, norms, values and governance.” From this perspective, if there is to be any chance to avoid climate catastrophe, climate change needs to be addressed through real, material changes in our global production systems, mechanisms of governance, and in the way we structure our economic systems and incentives. These changes need to be accompanied by cultural, societal, and normative changes, but those immaterial elements cannot stand alone. In short, we need to radically rethink how we produce society.

Here, the fact that games are, as mentioned above, in one way or another connected to many of the biggest sustainability issues we are currently facing, might also put us in a position to create positive change in many places. Especially digital gaming could be an influential starting point for said material as well as discursive sea-change.

This perspective already exists in the games industry. Taking again the data from the 2024 State of the Game Industry (GDC & Game Developer, 2023), the report chooses to cite a number of very interesting quotes, for example this one:

“They have been diligent but there is still the silent belief that ‘first we make money, then we clean after ourselves,’ without accepting that this is pretty much the mindset that brought the global society to this state. The environmental crisis seems a much larger problem that my current company believes to be able to tackle.”

This shows that there already is an understanding that the climate crisis and sustainability issues need to be addressed system-wide, with actions that go beyond the level of the individual studio. The quote also calls for us to not consider sustainability as an after-though but to treat it as a priority from the start. As a takeaway here, a sustainable games industry would have to be part and object of a radical and systemic change in how it operates. This change needs to also encompass the material world and needs to extend beyond discourse and discussion.

Impeding Transformation

However, the UN report also explains that “some attractive and feasible actions can impede transformation”, and transformation here means the fundamental change to how we build society that is mentioned in the paragraph above. As a mechanism for this impediment of transformation, the report explains that “The changes that appear most feasible may be those that do not contribute to, or even impede, transformative change, for instance by retaining or even consolidating the power interests vested in the status quo (see Section 5.3).” Here it says that “Some individuals and organizations also have substantial stakes in maintaining the status quo. These vested interests may oppose changes that disrupt their livelihoods, market shares and future revenues.” This is the United Nations stating two things:

1. People and groups in positions of power will obstruct meaningful and systemic climate action because it would impact their wealth.

2. They can distract us from focusing on the necessary systemic change through ineffective, but enticing alternative actions, e.g. greenwashing

Parts of this warning can be applied in a fairly straight-forward manner to digital games. Games are published by and played on the platforms of some of the most powerful and influential international corporations on the planet. They, at least in the short term, benefit from the continuation of the hardware race that they are currently winning. Chapter 5 will offer more pragmatic ways to think about systemic change and there we will come back to the responsibility of powerful actors and organizations.

Green Washing and Individualization – Why we need Collective Action

What are the “attractive and feasible actions [that] can impede transformation”? One way of understanding this formulation relates to a common narrative about climate change in both contemporary culture and games that presents it as the responsibility of individuals instead of groups and mostly a question of what we believe instead of how we collectively act. In a call for action, preceding the urgent warning of the United Nations by 20 years, Maniates states that “the forces that systematically individualize responsibility for environmental degradation must be challenged.” This narrative positions individuals and their actions as the final and sole responsible for climate catastrophe and, importantly, individual behavioral change as the only avenue for change. It disguises material and systemic problems as exclusively issues of individual virtue and character and makes it impossible to even consider the role of the vested industrial interests that benefit from the status quo, like the fossil fuel industries. This raises the question of whether the individualization of climate responsibility then is not only an involuntary consequence of neoliberalism, but a purposeful distraction and greenwashing by the fossil-fuel industry. Even the concept of the “carbon footprint” is a development of the Exxon Mobile concern as a distraction, so that we all focus on the responsibility of each individual instead of coming together to change the world. Again: The carbon footprint, the entire metaphor, is toxic greenwashing from oil companies. This is what the UN is warning us about, the vested interests benefiting from the maintenance of the system that is destroying the planet, and that those might hinder effective and systemic climate action.

Here then, the individualization of climate action can be seen as a kind of purposeful greenwashing: an attempt to create a narrative in which the systemic change of society cannot even be imagined, and so the necessary systemic and radical transformation becomes impossible to even consider. Maniates’s call might not have been meant to address games specifically, but it remains relevant while one of the proposed uses of games is the education of players. Research about sustainability education has shown that it is both possible and necessary to go beyond placing the responsibility for climate change at the feet of customers in a market and to address sustainability, together with the students, from a systemic and inter-disciplinary perspective. In addition, games are perfectly suited to portray the workings of systems and to open them up for critical reflection in ways that other media are incapable of. Educating players to see the workings of destructive and exploitative systems and the ways in which they are implicated (and the games they are currently playing are implicated) is definitely a good start and something that we will come back to later. However, the conclusion here for defining a sustainable games industry is that it has to resist individualization and include collective and organized action. This is also something that the industry on some level already understands.

“Others spoke to feelings of disillusionment, frustration, and helplessness when it comes to making a positive impact on the environment—especially related to the issue of personal versus collective responsibility.”

Beyond Discourse towards Material Change

It is a good step to show, also in the content and message of the games that we make, that we must approach sustainability questions collectively and that it is counterproductive to focus on individual responsibility. This is also typically the first thing we think about when considering games and sustainability. Games as culture can change the way players think and feel about their environment and can in this way create societal change. The possibility of changing the way players see the world and to inspire them towards systemic change is valid. That said, it should not be seen as a reason to keep polluting or being part of the systems that create climate change. It is not only about making games for sustainability, but also about making games sustainably. This is a central point, and one that other authors in this book discuss from different perspectives. David ten Cate discusses the need for ecological games to also consider how they are being made as a part of an economic system and Jennifer Estaris discusses from the view of a designer how she sees the potential of games for her concept of sea change and the connections of what is in our hearts and how we act. So how can we make sure that we together also take that next step, reach beyond discourse, and collectively change our systems?

Material and Collective Change

At the first planning meeting for the Nordic sustainability-themed game jam, a member of the Finnish game industry presented the work they had done to get their studio to address sustainability issues. Amazingly, and at that point ahead of their time, they included emissions by the players who were playing their game into the carbon emission calculations of their studio. These emissions during play are often one of the biggest sources of emissions related to digital games and considering these the responsibility of the studio shows an honest and real engagement for sustainability. They then bought carbon offsets from the highest-rated sellers that they could find to make up for their emissions. However, this is also where their efforts ended. First it is important to say that this is not intended as an example of a member of the game industry being naïve or doing something stupid. On the contrary, I would consider this an exemplary effort to do their part in addressing the climate crisis. That being said, it is important to also admit that, in this discursive prison of the individualization of climate responsibility that has been built in contemporary culture for decades, approaches to material change have also been only allowed to be imagined in limited ways. Here, material change starts and also ends with carbon offsets.

Carbon offsets have been heavily criticized for various reasons in research. Offsets frequently do not really work, binding carbon only for short periods but calculated as if the carbon would stay quasi-permanently bound, and with a lack of oversight are open for exploitation, cheating, and the continuation of the same colonial and logics that constitute the climate crisis. They even continue to perpetuate the mindset and system of trading the right to pollute, along with the mindset of individual customer responsibility that the polluting industries promote . At this point, issues with carbon offsets are so widely known, and in their worst excesses so absurd as to be funny, that they were a topic of the comedy show “Last Week Tonight” in 2022. At the time of writing in late 2024, we’re once again in a round of CEOs getting sued because their companies over-estimated their emission reductions by an average of 1000%. Here carbon offsetting is an example for the “attractive and feasible actions” that “can impede transformation.”

This shows that even a collective, systemic intervention like carbon trading and the offset industry can be insufficient or even something that impedes transformative change, especially if done instead of reducing energy use or a restructuring of technological infrastructure. The perspectives from the industry already share this conclusion.

“We do some carbon offsetting, but that feels like a Band-Aid on a bleeding wound. Not much is being done, or not that I know of, to address deeper issues like the energy consumption taken up with processor-intensive game development and maintaining our massive internal networks.”

This is why it was heartbreaking to see the honest and commendable effort of our Finnish colleague end with carbon offsets.

Thinking in “Systemic Change”

At the time when this happened, I was not prepared to offer real alternatives. Honestly, it would still be difficult. This speaks to how effective the individualization discourse is that we have difficulties even thinking about collective changes. Systemic change is tricky because we are used to the systems we live in, and it can be challenging to see a bigger picture. It also often requires some kind of safe space and trust to be able to pitch systemic change, because any suggestion of systemic change can frequently result in having to present and justify a ready and solved alternative system which is of course impossible to do. If the justifications that are demanded from any change and alternative are not also required from the status quo, which is currently destroying our planet to the point that the UN calls for fundamental change, then this indicates a bias towards the existing system that is likely in some way in the head of each of us, and possibly an unsafe space. This book then also tries to both offer some examples for what such change could look like, so that we can all use them in conversations and in our thinking, and it tries to grow the community of game workers who already care about this conversation and who can be this safe space for all of us.

In a later chapter I will offer more examples for collective, material, and systemic change that are meant to be starting points for finding new ways of meaningful climate action. This is work in progress.

But let us consider this example: Some games already offer an Eco Mode. This means that players can choose to play the game at lower performance to reduce emissions and energy costs. What if we argued, together, for legislation that required games to show the player a summary of their gaming energy use and estimated emissions at the end of each week, kind of like your phone shows you which apps drain your battery the most when it is about to die? Now we would take a first step into a conversation around the environmental responsibility of designers and players and start a competition for creating the most frugal games that get the most amazing performance out of the least amount of emissions. There could be collective achievements for players connected to the use of Eco Mode, and then at a later step, once we have built acceptance for eco modes, they could become industry default and even policy. This would be a longer process, but we have already taken the first steps and with our eyes set to collective, material and systemic change we can continue this path together.

Conclusion:

This chapter asked the question: “What would constitute successful and meaningful climate action in the games industry?”

Based on the discussion of industry feedback in connection to research and the reports of the United Nations, successful and meaningful climate action in the games industry would:

1. move from individual to collective responsibility and action

2. go beyond the discursive towards material change

3. resist greenwashing that (purposefully) impedes transformative change and

4. lead to systemic change in the way we produce society.

Returning to the story of the indie developer working on a sustainability game with money from Meta, I would like to argue that many of us can on some level relate to their experience. The results from the survey here also show people in the game industry are on some level aware that a lot of the sustainability work we are doing or are allowed to do can be either diverted by or even a part of greenwashing. This is where this chapter, and collectively this book, argues that we need an approach that centers around collective action to reach systemic and material goals. This is what this book is all about.

So, let’s get into it!

References

[1] Big tech has regrettably been combating EU regulation for a long time (Doctorow, 2024) and instead favours a self-regulation approach. However, “a critical approach is essential when evaluating Big Tech’s often deceptive sustainability narratives and underscores the need for more rigorous regulatory frameworks” (Vrikki, 2024:1) in all areas, but specifically around sustainability. “disclosure legislation, international soft law and private actors’ corporate sustainability codes of conduct. Despite an abundance of norms, egregious human and environmental rights violations […] continue.” (Zumbansen, 2024:1; about sustainability regulations in global value chains)

Cory Doctorow, “Big Tech to EU: ‘Drop Dead,’” Electronic Frontier Foundation, May 13, 2024, https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2024/05/big-tech-eu-drop-dead.

Photini Vrikki, “Measuring Up? The Illusion of Sustainability and the Limits of Big Tech Self-Regulation,” Sustainability 16, no. 23 (January 2024): 10197, https://doi.org/10.3390/su162310197.

Peer C. Zumbansen, “De-Valuing Sustainability: Financialized Disclosure Governance And Transparency In Modern Slavery And Climate Change,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, December 13, 2024), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5054382.

[1] Game Developers Conference and GameDeveloper.com (2023:24). 2024 State of the Game Industry.

[1] GDC & Game Developer, 2023.

[1] Clayton Whittle, Trevin York, Paula Angela Escuadra, Grant Shonkwiler, Hugo Bille, Arnaud Fayolle, Benn McGregor, Shayne Hayes, Felix Knight, Andrew Wills, Alenda Chang and Daniel Fernández Galeote, (2022). The Environmental Game Design Playbook (Presented by the IGDA Climate Special Interest Group). International Game Developers Association.

[1] Alenda Y. Chang, “Change for Games: On Sustainable Design Patterns for the (Digital) Future,” in Ecogames, by Laura Op De Beke et al. (Nieuwe Prinsengracht 89 1018 VR Amsterdam Nederland: Amsterdam University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463721196_ch01.

[1] Laura Op De Beke, Joost Raessens, Stefan Werning and Gerald Farca, (Eds.). (2024). Ecogames: Playful Perspectives on the Climate Crisis. (Nieuwe Prinsengracht 89 1018 VR Amsterdam Nederland: Amsterdam University Press, 2023), https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463721196_ch01.

[1] Clah of Realities Conference. Cologne, 2022. https://clashofrealities.com/2022/

[1] Patrick Prax, Clayton Whittle, Trevin York, Sonia Fizek. (2023) Educators Summit: Teaching Sustainability and Game Design: From the Low-Hanging Fruits to the Root of the Problem. GDC Educators Summit.

https://schedule.gdconf.com/session/educators-summit-teaching-sustainability-and-game-design-from-the-low-hanging-fruits-to-the-root-of-the-problem/891032/?_mc=edit_gdcsf_gdcsf_le_x_41_x_2023

[1] Benjamin J. Abraham, Digital Games After Climate Change, Palgrave Studies in Media and Environmental Communication (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91705-0.

[1] Greening Games Education_Report 2023. Google Docs. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1caJyVQ_Tcwzy8l_4bt1Zl3WN2u2hqR3Feb8M_UjGw8s/edit?usp=embed_facebook

[1] Sonia Fizek et al., “Teaching Environmentally Conscious Game Design: Lessons and Challenges,” Games: Research and Practice 1, no. 1 (March 12, 2023): 3:1-3:9, https://doi.org/10.1145/3583058.

[1] Hanna Wirman et al., “From ‘Doomsday Talks’ to ‘Excitement at Last’: A Case Study of Incorporating Sustainability Perspectives into Formal Game Education,” in Nordic DiGRA Conference 2023, Uppsala, 27–28 April 2023, 2023, 1–10, https://pure.itu.dk/files/100885374/NoDigra_2023_paper_7722.pdf.

[1] Abraham, 2022.

[1] Patrick Prax, “Are the Bullets Going over Our Head? Designed Ambivalence in the Representation of Armed Conflict in Games,” in Representing Conflicts in Games (Routledge, 2022), 153–70, https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781003297406-13/bullets-going-head-designed-ambivalence-representation-armed-conflict-games-patrick-prax.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme [UNEP] (2021). Making Peace with Nature. A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies, Nairobi, https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature. Page 13.

[1] GDC & Game Developer, 2023.

[1]United Nations Environment Programme, 2021. Page 113.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, 2021. Page 114.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, 2021. Page 104.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, 2021.

[1] Michael F. Maniates, “Individualization: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World?,” Global Environmental Politics 1, no. 3 (2001): 31–52.

[1] Maniates, 2001.

[1] Jennifer Kent, “Individualized Responsibility and Climate Change:’If Climate Protection Becomes Everyone’s Responsibility, Does It End up Being No-One’s?’,” Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 1, no. 3 (2009): 132–49.

[1] Magali A. Delmas and Vanessa Cuerel Burbano, “The Drivers of Greenwashing,” California Management Review 54, no. 1 (2011): 64–87.

[1] William S. Laufer, “Social Accountability and Corporate Greenwashing,” Journal of Business Ethics 43, no. 3 (2003): 253–61.

[1] Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes, “Rhetoric and Frame Analysis of ExxonMobil’s Climate Change Communications,” One Earth 4, no. 5 (2021): 696–719.

[1] Maniates, 2001.

[1] Jo-Anne Ferreira, “The Limits of Environmental Educators’ Fashioning of ‘Individualized’ Environmental Citizens,” The Journal of Environmental Education 50, no. 4–6 (December 2, 2019): 321–31, https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2019.1721769.

[1] Jo-Anne Ferreira, Vicki Keliher, and Jessica Blomfield, “Becoming a Reflective Environmental Educator: Students’ Insights on the Benefits of Reflective Practice,” Reflective Practice 14, no. 3 (June 1, 2013): 368–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.767233.

[1] Elina Eriksson et al., “Addressing Students’ Eco-Anxiety When Teaching Sustainability in Higher Education,” in 2022 International Conference on ICT for Sustainability (ICT4S), 2022, 88–98, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICT4S55073.2022.00020.

[1] Ian Bogost, “Persuasive Games, a Decade Later,” Persuasive Gaming in Context, 2021, 29–40.

[1] Michael Mateas, “Procedural Literacy: Educating the New Media Practitioner,” On the Horizon 13, no. 2 (2005): 101–11.

[1] Dennis Meadows, Linda Booth Sweeney, and Gillian Martin Mehers, The Climate Change Playbook: 22 Systems Thinking Games for More Effective Communication about Climate Change (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2016), https://books.google.com/books?hl=sv&lr=&id=BxMRDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=games+and+system+thinking&ots=XwsIOqQb7c&sig=Nby_ZhAcvTDmIrIYqJ8MXAEA20Y.

[1] Pejman Sajjadi et al., “Promoting Systems Thinking and Pro-Environmental Policy Support through Serious Games,” Frontiers in Environmental Science 10 (2022): 957204.

[1] GDC & Game Developer, 2023.

[1] Inés Acosta, “‘Green Desert’ Monoculture Forests Spreading in Africa and South America,” The Guardian, September 26, 2011, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/sep/26/monoculture-forests-africa-south-america.

[1] David Bickford et al., “Science Communication for Biodiversity Conservation,” Biological Conservation, ADVANCING ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION: ESSAYS IN HONOR OF NAVJOT SODHI, 151, no. 1 (July 1, 2012): 74–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.12.016.

[1] Daniel J. Sherman, “Upsetting the Offset: The Political Economy of Carbon Markets,” Social Movement Studies 12, no. 3 (2013): 354–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2013.787766.

[1] Steffen Böhm, Maria Ceci Misoczky, and Sandra Moog, “Greening Capitalism? A Marxist Critique of Carbon Markets,” Organization Studies 33, no. 11 (November 2012): 1617–38, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612463326.

[1] Adrian Horton, “John Oliver on Corporate ‘Net Zero’ Proposals: ‘We Cannot Offset Our Way out of Climate Change,’” The Guardian, August 22, 2022, sec. Television & radio, https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2022/aug/22/john-oliver-net-zero-climate-change-last-week-tonight.

[1] Patrick Greenfield, “Ex-Carbon Offsetting Boss Charged in New York with Multimillion-Dollar Fraud,” The Guardian, October 4, 2024, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/oct/04/ex-carbon-offsetting-boss-kenneth-newcombe-charged-in-new-york-with-multimillion-dollar.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme, 2021.

[1] GDC & Game Developer, 2023.